The educational system of Germany is underlying to continuous changes and reforms. Main point in the last years was the reorganization of the Gymnasium. The nine year education was changed into an eight year education to get the Abitur. Furthermore, the academic system had changed because of the Bologna reform. The degrees obtained are now called Bachelor and Master.

Studying in Germany requires the graduate degree Abitur or the advanced technical college entrance qualification. International students have to show a similar graduate degree. Until now it was not possible to build a central organization for application and award of university places. Because of this the applications still need to be sent to every university or advanced technical college.

The admission requirements are also defined by the universities. Therefore, they can be different for the same subjects at different universities. In Germany there are three different kinds of advanced colleges or universities. Arts, film or music advanced colleges offer practical education in the artistic subjects. Advanced technical colleges however, cover the scientific and social subjects. They also set value on practical experiences in their education. The third category is the so called university. They offer all different kinds of subjects. Practical experience is an important point as well but the universities are especially famous for their firm theoretical education.

Another differentiation can be made between public and private universities. Public universities are financed by the government and do not charge tuition fees or just small amounts of money. Private universities in contrast are financed by the fees paid by students and these can be quite expensive. In Germany can be found much more public universities than there are private ones. German law says that education should be offered to everyone and everyone should be able to afford adequate education. Therefore, in some areas tuition fees were abolished in other areas they are very small. Moreover, there are numerous possibilities to get help from the government, for example Bafög-money.

The studies in Germany are in some aspects more theoretical than in other countries and they consist of many lectures from the professor. In the lecture there are all students of one year and there are just a few exercise lessons in which the theoretical part can be practiced and proofed in reality. At the end of every term the students get grades for their final examination and for speeches, assignments and practical projects. Depending on the subject the composition of these parts can differ. Practical education can also be offered in internships which are an obligation in some subjects. For some weeks or months the students have to work in a company and use their theoretical knowledge in real life situations to gain experience. This is also a good chance to find a job for the working life after university. The graduate degrees from university are accepted and estimated worldwide. The education at German universities is considered as a good one. The first graduate degree can be obtained after six to eight terms and is called Bachelor.

Afterwards it is followed by the Master degree after another two to four terms. Both degrees require passing the exams and writing a specific graduate thesis. For the subjects medicine, dentistry, law and pharmaceutics as well as the teaching degree another degree is required which is called Staatsexamen. After the Master degree students can also do their graduation to get their doctor’s degree. Academic education in Germany should give firm basic knowledge and theoretical background as well as specific details and practical application. After successful studies the alumni should be able to work successful in every part of the working environment.

Related Articels :

Education System In Finland - Why Are Finland's Schools Successful?

Basic Education System In Japan

Education System In South Korean

Education System in China

Education System In United States

Showing posts with label Education System. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Education System. Show all posts

Education System In Finland - Why Are Finland's Schools Successful?

|

| "This is what we do every day," says Kirkkojarvi Comprehensive School principal Kari Louhivuori, "prepare kids for life." (Stuart Conway) |

Finland has vastly improved in reading, math and science literacy over the past decade in large part because its teachers are trusted to do whatever it takes to turn young lives around. This 13-year-old, Besart Kabashi, received something akin to royal tutoring.

“I took Besart on that year as my private student,” Louhivuori told me in his office, which boasted a Beatles “Yellow Submarine” poster on the wall and an electric guitar in the closet. When Besart was not studying science, geography and math, he was parked next to Louhivuori’s desk at the front of his class of 9- and 10-year- olds, cracking open books from a tall stack, slowly reading one, then another, then devouring them by the dozens. By the end of the year, the son of Kosovo war refugees had conquered his adopted country’s vowel-rich language and arrived at the realization that he could, in fact, learn.

Years later, a 20-year-old Besart showed up at Kirkkojarvi’s Christmas party with a bottle of Cognac and a big grin. “You helped me,” he told his former teacher. Besart had opened his own car repair firm and a cleaning company. “No big fuss,” Louhivuori told me. “This is what we do every day, prepare kids for life.”

This tale of a single rescued child hints at some of the reasons for the tiny Nordic nation’s staggering record of education success, a phenomenon that has inspired, baffled and even irked many of America’s parents and educators. Finnish schooling became an unlikely hot topic after the 2010 documentary film Waiting for “Superman” contrasted it with America’s troubled public schools.

“Whatever it takes” is an attitude that drives not just Kirkkojarvi’s 30 teachers, but most of Finland’s 62,000 educators in 3,500 schools from Lapland to Turku—professionals selected from the top 10 percent of the nation’s graduates to earn a required master’s degree in education. Many schools are small enough so that teachers know every student. If one method fails, teachers consult with colleagues to try something else. They seem to relish the challenges. Nearly 30 percent of Finland’s children receive some kind of special help during their first nine years of school. The school where Louhivuori teaches served 240 first through ninth graders last year; and in contrast with Finland’s reputation for ethnic homogeneity, more than half of its 150 elementary-level students are immigrants—from Somalia, Iraq, Russia, Bangladesh, Estonia and Ethiopia, among other nations. “Children from wealthy families with lots of education can be taught by stupid teachers,” Louhivuori said, smiling. “We try to catch the weak students. It’s deep in our thinking.”

The transformation of the Finns’ education system began some 40 years ago as the key propellent of the country’s economic recovery plan. Educators had little idea it was so successful until 2000, when the first results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a standardized test given to 15-year-olds in more than 40 global venues, revealed Finnish youth to be the best young readers in the world. Three years later, they led in math. By 2006, Finland was first out of 57 countries (and a few cities) in science. In the 2009 PISA scores released last year, the nation came in second in science, third in reading and sixth in math among nearly half a million students worldwide. “I’m still surprised,” said Arjariita Heikkinen, principal of a Helsinki comprehensive school. “I didn’t realize we were that good.”

Education System In the United States, which has muddled along in the middle for the past decade, government officials have attempted to introduce marketplace competition into public schools. In recent years, a group of Wall Street financiers and philanthropists such as Bill Gates have put money behind private-sector ideas, such as vouchers, data-driven curriculum and charter schools, which have doubled in number in the past decade. President Obama, too, has apparently bet on competition. His Race to the Top initiative invites states to compete for federal dollars using tests and other methods to measure teachers, a philosophy that would not fly in Finland. “I think, in fact, teachers would tear off their shirts,” said Timo Heikkinen, a Helsinki principal with 24 years of teaching experience. “If you only measure the statistics, you miss the human aspect.”

Related Aricles :

Education System in China

Education System In U.S.A

Basic Education System In Japan

Basic Education System In Japan

The school year begins in April, although there is a long break in the summer. One school year begins in April with the first term, has a month off from school for summer break, followed by another term which is followed by a winter break. The final term ends with a spring break before the next school year begins that following April.

Preschool and kindergarten are not considered “compulsory” in the Japanese education system, but are available. Kindergartens may offer a one-, two-, or three-year program depending on the age of the child upon entry.

Elementary school and middle school (junior high) are compulsory; in other words, they are required by law for all Japanese citizens. In the U.S. grades K through 12 are considered compulsory, though high school students may withdraw from school after age 16 with the option to seek a GED (general education diploma).

High school in Japan is not compulsory. This means that not only are students not required to go to high school, but if a family wishes their child to attend high school there will be a tuition involved, like private school or college. To get into a high school, students begin early in their final year of middle school, preparing for high school entrance exams. Getting into high school is comparable to applying for colleges, and the competition is very steep. If the student applies for only one high school and fails the entrance exam, that student has to wait until the following year before able to apply and take entrance exams for other schools. For this reason, just like with college, many students take exams for several schools just in case.

Students whose families can afford prep school may attend extra preparatory classes after their regular middle school classes to help prepare for entrance exams for high schools. In many ways, the Japanese consider entering high school more difficult than entering colleges due to the competition. Still, an estimated 90% of Japanese students graduate from high school.

Vocabulary

- Hoikuen Preschool

- Youchien Kindergarten

- Shougakkou Elementary School

- Chuugakkou Middle School

- Koukou High School

- Juku Cram School, Prep School (for entrance exams)

Education System In South Korean

iPhone 5 or Samsung Galaxy S3 is now the choice that many consumers are facing these days.

On one hand you have the iPhone: a sleek, refined product of American innovation, a phone touted by enthusiastic techies and laymen as simply the most revolutionary phone product to hit the market. On the other you have Galaxy S3, which generated enough excitement in its early stages of development for many to dub it the ‘iPhone killer’. It is an amalgamation of cherry-picked features, slight alterations, and excellent execution.

After a high-profile patent case, Samsung was forced to pay over $1 billion in damages for infringing upon a number of Apple designs and patents. Nonetheless, Samsung’s business model of essentially “playing catch-up” to Apple and improving on Apple’s designs ended up paying off. In Q3 2012, the Samsung Galaxy S3 beat out the iPhone 4S (an older model) to become the world’s best-selling smartphone.

At their core, the business strategies of Apple and Samsung Electronics represent fundamental differences in thinking and attitude. The anti-corporate culture of Apple, as embodied by the image of a barefoot Steve Jobs, versus the massive, South Korean conglomerate (chaebol) Samsung Electronics.

While much could be said about how individuals have shaped their separate corporate philosophies, and in turn their trajectories, perhaps we can take a look at the intellectual and academic environments in which these two corporations formed. Perhaps Samsung’s ability to copy rather than innovate is reflective of South Korea’s education system, which many say is top-notch but doesn’t nurture creative thinkers.

A recent study done by an education research firm, Pearson, places South Korea among the most well-educated countries in the world. Considering how well South Korean students have traditionally fared on standardized reading and math tests, the results of this recent study are certainly no surprise. In contrast, the U.S. is a middle-of-the-road country when it comes to education, despite its status as the leading economic power in the world.

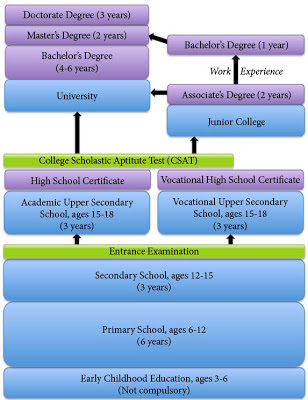

Educational spending could be one cause of this achievement gap. According to the Center on International Education Benchmarking, South Korea spends 7.6% of its GDP on education, the second highest among OECD countries. Intense schooling starts from the age of 6, culminating in the College Scholastic Aptitude Test, a high-stakes college admissions test that often determines one’s future financial, social, and personal success. The average Korean student attends regular schooling in addition to “cram schools,” private after-school academies that specialize in skills ranging from English and math to playing an instrument. Nearly 9% of children are forced to attend such places past 11pm.

For all the success that the South Korean system has produced, it has many flaws. Consequences of such a high pressure educational system manifest themselves in all sorts of manners including the abnormally high prevalence of youth suicides and poor social skills.

Furthermore, in such a system it is difficult to cultivate innovative and creative thinkers. Instead of valuing individualism and unconventional thinking, children are taught at a very young age that memorization and brute repetition will lead to good grades, admissions into prestigious universities, and a successful life.

Former South Korean minister of education, Byong-man Ahn, notes, “Students have no time to ponder the fundamental question of ‘What do I need to learn, and why?’ They simply need to prepare for the test by learning the most-effective methods for digesting tremendous quantities of material and committing more to memory than others do.”

The South Korean government is currently in the process of implementing reforms that it hopes will help foster creativity. Such reforms include reducing material students need to study and refining the ways teachers engage their classes. Interestingly enough, the government itself may be the cause of the educational system’s problems. The Ministry of Education develops a national curriculum that is then disseminated to nearly all of South Korea’s primary schools. The fact that educational reform is implemented from the top-down may discourage experimentation with more effective forms of learning, such as a switch to more hands-on activities and a greater degree of freedom for students to pursue their own academic interests.

Furthermore, while there is reason to be optimistic, such reforms may not be enough. In order to truly foster a nation of innovators and outside-the-box thinkers, South Korea may need an entire cultural shift. The social stigma against those unable to gain entrance into a prestigious university may be forcing creative thinkers to focus all their time on brute memorization, which in turn could push them into despair.

It may be years before South Korea can champion its own Silicon Valley. It would take nothing short of a complete revamp of education and a cultural shift that promotes individuality and iconoclastic thinking to produce an environment conducive to producing the Steve Jobs of tomorrow. But for now we all may have to make do with products like the Samsung Galaxy S3; effective but not groundbreaking.

Related Articles :

Education System In American

Education System in Chinesse

On one hand you have the iPhone: a sleek, refined product of American innovation, a phone touted by enthusiastic techies and laymen as simply the most revolutionary phone product to hit the market. On the other you have Galaxy S3, which generated enough excitement in its early stages of development for many to dub it the ‘iPhone killer’. It is an amalgamation of cherry-picked features, slight alterations, and excellent execution.

After a high-profile patent case, Samsung was forced to pay over $1 billion in damages for infringing upon a number of Apple designs and patents. Nonetheless, Samsung’s business model of essentially “playing catch-up” to Apple and improving on Apple’s designs ended up paying off. In Q3 2012, the Samsung Galaxy S3 beat out the iPhone 4S (an older model) to become the world’s best-selling smartphone.

At their core, the business strategies of Apple and Samsung Electronics represent fundamental differences in thinking and attitude. The anti-corporate culture of Apple, as embodied by the image of a barefoot Steve Jobs, versus the massive, South Korean conglomerate (chaebol) Samsung Electronics.

While much could be said about how individuals have shaped their separate corporate philosophies, and in turn their trajectories, perhaps we can take a look at the intellectual and academic environments in which these two corporations formed. Perhaps Samsung’s ability to copy rather than innovate is reflective of South Korea’s education system, which many say is top-notch but doesn’t nurture creative thinkers.

A recent study done by an education research firm, Pearson, places South Korea among the most well-educated countries in the world. Considering how well South Korean students have traditionally fared on standardized reading and math tests, the results of this recent study are certainly no surprise. In contrast, the U.S. is a middle-of-the-road country when it comes to education, despite its status as the leading economic power in the world.

Educational spending could be one cause of this achievement gap. According to the Center on International Education Benchmarking, South Korea spends 7.6% of its GDP on education, the second highest among OECD countries. Intense schooling starts from the age of 6, culminating in the College Scholastic Aptitude Test, a high-stakes college admissions test that often determines one’s future financial, social, and personal success. The average Korean student attends regular schooling in addition to “cram schools,” private after-school academies that specialize in skills ranging from English and math to playing an instrument. Nearly 9% of children are forced to attend such places past 11pm.

For all the success that the South Korean system has produced, it has many flaws. Consequences of such a high pressure educational system manifest themselves in all sorts of manners including the abnormally high prevalence of youth suicides and poor social skills.

Furthermore, in such a system it is difficult to cultivate innovative and creative thinkers. Instead of valuing individualism and unconventional thinking, children are taught at a very young age that memorization and brute repetition will lead to good grades, admissions into prestigious universities, and a successful life.

Former South Korean minister of education, Byong-man Ahn, notes, “Students have no time to ponder the fundamental question of ‘What do I need to learn, and why?’ They simply need to prepare for the test by learning the most-effective methods for digesting tremendous quantities of material and committing more to memory than others do.”

The South Korean government is currently in the process of implementing reforms that it hopes will help foster creativity. Such reforms include reducing material students need to study and refining the ways teachers engage their classes. Interestingly enough, the government itself may be the cause of the educational system’s problems. The Ministry of Education develops a national curriculum that is then disseminated to nearly all of South Korea’s primary schools. The fact that educational reform is implemented from the top-down may discourage experimentation with more effective forms of learning, such as a switch to more hands-on activities and a greater degree of freedom for students to pursue their own academic interests.

Furthermore, while there is reason to be optimistic, such reforms may not be enough. In order to truly foster a nation of innovators and outside-the-box thinkers, South Korea may need an entire cultural shift. The social stigma against those unable to gain entrance into a prestigious university may be forcing creative thinkers to focus all their time on brute memorization, which in turn could push them into despair.

It may be years before South Korea can champion its own Silicon Valley. It would take nothing short of a complete revamp of education and a cultural shift that promotes individuality and iconoclastic thinking to produce an environment conducive to producing the Steve Jobs of tomorrow. But for now we all may have to make do with products like the Samsung Galaxy S3; effective but not groundbreaking.

Related Articles :

Education System In American

Education System in Chinesse

Education System in China

The education system in the People's Republic of China is state-run, under the authority of the Ministry of Education. Education has always been valued by the Chinese, and it is considered one of the foundations of public order and civilized life.

The idea that merit and ability are more important than race or birth in state appointments was popular in China as early as the classical era (600 - 250 BCE). Despite this, for a long time only the wealthy and aristocrats had the privilege of receiving education. The Chinese created the first examination system for selecting officials during the Tang (618 - 906) and Song (960 - 1280) dynasties. In medieval China there were also charitable institutions established by Buddhists, including temple schools, that offered education for common people, both men and women.

Imperial China established a nationwide government school system in 3 CE under Emperor Ping of Han, centuries before this happened in Europe. However, this school system was not aimed at providing mass education but was strongly connected to the government examinations for recruiting officials for civil or military service. The government committed financially to the schools, which provided education in classical learning, painting, literature and calligraphy. One by-product of this system was an elite that produced poetry and other literature as well as scholarly works including medical treatises.

The fact that dynastic schools were used for moral and political indoctrination by the imperial state led to the emergence of private academies that often became centers for dissenting views. By the end of the Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644), there were up to 2,000 private academies in China. At that time Neo-Confucianism, which attempted to merge certain basic elements of Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism, was common throughout the empire. During the Qing dynasty (1644 - 1912), also known as the Manchu dynasty, and China's last imperial period, the number of private academies increased to around 4,000.

While in Ming China elite status and commercial wealth were firmly linked to high educational status, in contemporary Europe and Japan there were absolute social barriers between aristocrats and commoners. However, as education was not available to common people in China, they could not really take advantage of this openness of the civil service. In addition, there was a clear demarcated line between male and female upbringing. It was not until the 17th century when educating women in classical literacy, or the ability to write elegant essays and poetry, became more common in elite families.

The Manchu rulers used dynastic schools and examinations as a means of cultural control, rather than as a means to promote public literacy. The government's examination system was falling apart by the beginning of the 20th century, when dynastic imperial power weakened. The beginning of the end for China as an empire was marked by the Russo-Japanese War (1904 - 1905), which was largely fought on Chinese soil. Following a common memorial submitted by court and provincial officials government examinations, which were seen as an obstacle to new schools, were abolished at all levels. In December 1905 an Education Board was established and took responsibility for the new schools. This board also monitored the work of the many newly established semi-official educational associations on the local and regional levels.

In the 1980s, under the leadership of the post-Mao Zedong communist party, education in China underwent serious reforms, as it had become one of the country's highest priorities. The government viewed education as the foundation of the Four Modernizations, goals to modernize the country in the fields of agriculture, industry, national defense and science and technology.

By the early 21st century, education in China had been divided into three categories - basic, higher and adult education, according to the China Education and Research Network. Basic education in China includes preschool education, between the ages of 3 and 6, followed by six years of primary education, and secondary education of another six years. Since 1986 all Chinese children must get at least nine years of formal education, which means that primary school and junior secondary school are obligatory. Senior secondary education, which lasts for three years, is not compulsory.

The idea that merit and ability are more important than race or birth in state appointments was popular in China as early as the classical era (600 - 250 BCE). Despite this, for a long time only the wealthy and aristocrats had the privilege of receiving education. The Chinese created the first examination system for selecting officials during the Tang (618 - 906) and Song (960 - 1280) dynasties. In medieval China there were also charitable institutions established by Buddhists, including temple schools, that offered education for common people, both men and women.

Imperial China established a nationwide government school system in 3 CE under Emperor Ping of Han, centuries before this happened in Europe. However, this school system was not aimed at providing mass education but was strongly connected to the government examinations for recruiting officials for civil or military service. The government committed financially to the schools, which provided education in classical learning, painting, literature and calligraphy. One by-product of this system was an elite that produced poetry and other literature as well as scholarly works including medical treatises.

The fact that dynastic schools were used for moral and political indoctrination by the imperial state led to the emergence of private academies that often became centers for dissenting views. By the end of the Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644), there were up to 2,000 private academies in China. At that time Neo-Confucianism, which attempted to merge certain basic elements of Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism, was common throughout the empire. During the Qing dynasty (1644 - 1912), also known as the Manchu dynasty, and China's last imperial period, the number of private academies increased to around 4,000.

While in Ming China elite status and commercial wealth were firmly linked to high educational status, in contemporary Europe and Japan there were absolute social barriers between aristocrats and commoners. However, as education was not available to common people in China, they could not really take advantage of this openness of the civil service. In addition, there was a clear demarcated line between male and female upbringing. It was not until the 17th century when educating women in classical literacy, or the ability to write elegant essays and poetry, became more common in elite families.

The Manchu rulers used dynastic schools and examinations as a means of cultural control, rather than as a means to promote public literacy. The government's examination system was falling apart by the beginning of the 20th century, when dynastic imperial power weakened. The beginning of the end for China as an empire was marked by the Russo-Japanese War (1904 - 1905), which was largely fought on Chinese soil. Following a common memorial submitted by court and provincial officials government examinations, which were seen as an obstacle to new schools, were abolished at all levels. In December 1905 an Education Board was established and took responsibility for the new schools. This board also monitored the work of the many newly established semi-official educational associations on the local and regional levels.

In the 1980s, under the leadership of the post-Mao Zedong communist party, education in China underwent serious reforms, as it had become one of the country's highest priorities. The government viewed education as the foundation of the Four Modernizations, goals to modernize the country in the fields of agriculture, industry, national defense and science and technology.

By the early 21st century, education in China had been divided into three categories - basic, higher and adult education, according to the China Education and Research Network. Basic education in China includes preschool education, between the ages of 3 and 6, followed by six years of primary education, and secondary education of another six years. Since 1986 all Chinese children must get at least nine years of formal education, which means that primary school and junior secondary school are obligatory. Senior secondary education, which lasts for three years, is not compulsory.

Education System In U.S.A

Post Secondary Education in the U.S.

Post secondary education in the United States refers to all formal education beyond secondary school.

For international students seeking higher educational opportunities in the U.S., post secondary education is typically divided into the following categories :

Associate's Degree

Undergraduate Degree

Graduate Education (Master’s and Ph.D.)

Types of U.S. Higher Education Degrees Associate Degree

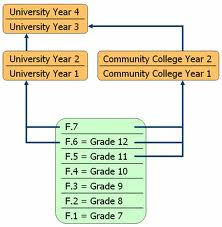

An Associate's Degree can be pursued after finishing 12 years of school education. These programs are usually offered by community colleges or junior colleges. These programs may vary from specialized technical programs to liberal arts degrees designed to lead to transfer into four-year Bachelor’s degree programs. Most public two-year colleges have articulation agreements with four-year institutions.

The Associate's Degree program is usually a two-year qualification in areas such as accounting, business, photography, interior designing, and the like.

Undergraduate Degree (B.A.)

Undergraduate education is pursued after finishing 12 years of school education successfully. It is offered in public and private colleges and universities as well as two-year institutions.

The curriculum of an undergraduate program generally consists of four general areas of study - major, cognates, general education courses and electives. The program is fairly flexible within subject groups, which enables a student to have numerous degree options, open in the year 1 and 2 of full-time study. In general, an undergraduate program can be finished successfully in four years.

Graduate Education (Master’s and Ph.D.)

Graduate education is pursued after successfully completing a Bachelor’s and/or Master’s degree. Master’s/Ph.D. programs of study are typically offered by universities and research institutes.

A graduate program could be research-based, coursework-based or can have a combination of both. In general, a Master’s program can be finished successfully in 1 or 2 years full-time. Master of Arts (M.A.) and Master of Science (M.S.) degrees are typically awarded in the traditional arts, sciences, and humanities disciplines. An M.S. degree is offered mostly in technical fields such as engineering, business and education.

Students who want to advance their education even further in a specific field can pursue a more specialized degree which is the doctorate degree, also called a Ph.D.. A Ph.D. degree can take between three and six years to complete, depending on the research area, the individual's ability, and the thesis that the student has selected. Doctoral level degree or Ph.D. (Doctor of Philosophy) is the highest degree awarded in academic disciplines. Some other professional doctoral degrees are: Ed.D. (Doctor of Education), D.B.A.m (Doctor of Business Administration), and M.D. (Doctor of Medicine).

Post secondary education in the United States refers to all formal education beyond secondary school.

For international students seeking higher educational opportunities in the U.S., post secondary education is typically divided into the following categories :

Types of U.S. Higher Education Degrees Associate Degree

An Associate's Degree can be pursued after finishing 12 years of school education. These programs are usually offered by community colleges or junior colleges. These programs may vary from specialized technical programs to liberal arts degrees designed to lead to transfer into four-year Bachelor’s degree programs. Most public two-year colleges have articulation agreements with four-year institutions.

The Associate's Degree program is usually a two-year qualification in areas such as accounting, business, photography, interior designing, and the like.

Undergraduate Degree (B.A.)

Undergraduate education is pursued after finishing 12 years of school education successfully. It is offered in public and private colleges and universities as well as two-year institutions.

The curriculum of an undergraduate program generally consists of four general areas of study - major, cognates, general education courses and electives. The program is fairly flexible within subject groups, which enables a student to have numerous degree options, open in the year 1 and 2 of full-time study. In general, an undergraduate program can be finished successfully in four years.

Graduate Education (Master’s and Ph.D.)

Graduate education is pursued after successfully completing a Bachelor’s and/or Master’s degree. Master’s/Ph.D. programs of study are typically offered by universities and research institutes.

A graduate program could be research-based, coursework-based or can have a combination of both. In general, a Master’s program can be finished successfully in 1 or 2 years full-time. Master of Arts (M.A.) and Master of Science (M.S.) degrees are typically awarded in the traditional arts, sciences, and humanities disciplines. An M.S. degree is offered mostly in technical fields such as engineering, business and education.

Students who want to advance their education even further in a specific field can pursue a more specialized degree which is the doctorate degree, also called a Ph.D.. A Ph.D. degree can take between three and six years to complete, depending on the research area, the individual's ability, and the thesis that the student has selected. Doctoral level degree or Ph.D. (Doctor of Philosophy) is the highest degree awarded in academic disciplines. Some other professional doctoral degrees are: Ed.D. (Doctor of Education), D.B.A.m (Doctor of Business Administration), and M.D. (Doctor of Medicine).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)