iPhone 5 or Samsung Galaxy S3 is now the choice that many consumers are facing these days.

On one hand you have the iPhone: a sleek, refined product of American innovation, a phone touted by enthusiastic techies and laymen as simply the most revolutionary phone product to hit the market. On the other you have Galaxy S3, which generated enough excitement in its early stages of development for many to dub it the ‘iPhone killer’. It is an amalgamation of cherry-picked features, slight alterations, and excellent execution.

After a high-profile patent case, Samsung was forced to pay over $1 billion in damages for infringing upon a number of Apple designs and patents. Nonetheless, Samsung’s business model of essentially “playing catch-up” to Apple and improving on Apple’s designs ended up paying off. In Q3 2012, the Samsung Galaxy S3 beat out the iPhone 4S (an older model) to become the world’s best-selling smartphone.

At their core, the business strategies of Apple and Samsung Electronics represent fundamental differences in thinking and attitude. The anti-corporate culture of Apple, as embodied by the image of a barefoot Steve Jobs, versus the massive, South Korean conglomerate (chaebol) Samsung Electronics.

While much could be said about how individuals have shaped their separate corporate philosophies, and in turn their trajectories, perhaps we can take a look at the intellectual and academic environments in which these two corporations formed. Perhaps Samsung’s ability to copy rather than innovate is reflective of South Korea’s education system, which many say is top-notch but doesn’t nurture creative thinkers.

A recent study done by an education research firm, Pearson, places South Korea among the most well-educated countries in the world. Considering how well South Korean students have traditionally fared on standardized reading and math tests, the results of this recent study are certainly no surprise. In contrast, the U.S. is a middle-of-the-road country when it comes to education, despite its status as the leading economic power in the world.

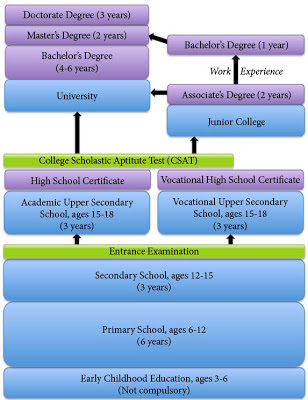

Educational spending could be one cause of this achievement gap. According to the Center on International Education Benchmarking, South Korea spends 7.6% of its GDP on education, the second highest among OECD countries. Intense schooling starts from the age of 6, culminating in the College Scholastic Aptitude Test, a high-stakes college admissions test that often determines one’s future financial, social, and personal success. The average Korean student attends regular schooling in addition to “cram schools,” private after-school academies that specialize in skills ranging from English and math to playing an instrument. Nearly 9% of children are forced to attend such places past 11pm.

For all the success that the South Korean system has produced, it has many flaws. Consequences of such a high pressure educational system manifest themselves in all sorts of manners including the abnormally high prevalence of youth suicides and poor social skills.

Furthermore, in such a system it is difficult to cultivate innovative and creative thinkers. Instead of valuing individualism and unconventional thinking, children are taught at a very young age that memorization and brute repetition will lead to good grades, admissions into prestigious universities, and a successful life.

Former South Korean minister of education, Byong-man Ahn, notes, “Students have no time to ponder the fundamental question of ‘What do I need to learn, and why?’ They simply need to prepare for the test by learning the most-effective methods for digesting tremendous quantities of material and committing more to memory than others do.”

The South Korean government is currently in the process of implementing reforms that it hopes will help foster creativity. Such reforms include reducing material students need to study and refining the ways teachers engage their classes. Interestingly enough, the government itself may be the cause of the educational system’s problems. The Ministry of Education develops a national curriculum that is then disseminated to nearly all of South Korea’s primary schools. The fact that educational reform is implemented from the top-down may discourage experimentation with more effective forms of learning, such as a switch to more hands-on activities and a greater degree of freedom for students to pursue their own academic interests.

Furthermore, while there is reason to be optimistic, such reforms may not be enough. In order to truly foster a nation of innovators and outside-the-box thinkers, South Korea may need an entire cultural shift. The social stigma against those unable to gain entrance into a prestigious university may be forcing creative thinkers to focus all their time on brute memorization, which in turn could push them into despair.

It may be years before South Korea can champion its own Silicon Valley. It would take nothing short of a complete revamp of education and a cultural shift that promotes individuality and iconoclastic thinking to produce an environment conducive to producing the Steve Jobs of tomorrow. But for now we all may have to make do with products like the Samsung Galaxy S3; effective but not groundbreaking.

Related Articles :

Education System In American

Education System in Chinesse